Christmas and its History

And she will bring forth a Son, and you shall call His name JESUS, for He will save His people from their sins.

What is really Christmas?

Christmas, Christian festival celebrating the birth of Jesus. The English term Christmas (“mass on Christ’s day”) is of fairly recent origin. Yule’s earlier term may have derived from the Germanic jōl or the Anglo-Saxon geōl, which referred to the winter solstice feast. The corresponding terms in other languages—Navidad in Spanish, Natale in Italian, Noël in French—probably denote nativity. The German word Weihnachten denotes, “hallowed night.”

Christmas, Christian festival celebrating the birth of Jesus. The English term Christmas (“mass on Christ’s day”) is of fairly recent origin. Yule’s earlier term may have derived from the Germanic jōl or the Anglo-Saxon geōl, which referred to the winter solstice feast. The corresponding terms in other languages—Navidad in Spanish, Natale in Italian, Noël in French—probably denote nativity. The German word Weihnachten denotes, “hallowed night.”

Christmas is celebrated on 25 December and is at the same time a sacred religious feast and a cultural and commercial phenomenon all over the world. For two millennia, people worldwide have been observing it with traditions and practices that are both religious and secular in nature. Christians celebrate Christmas Day as the anniversary of the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, a spiritual leader whose teachings form the basis of their religion.

Popular customs include exchanging gifts, decorating Christmas trees, attending church, sharing meals with family and friends, and, of course, waiting for Santa Claus to arrive.

How Did Christmas Start?

The middle of winter has long been a time of celebration around the world. Centuries before the arrival of the man called Jesus, early Europeans celebrated light and birth in the winter’s darkest days. Many peoples rejoiced during the winter solstice when the worst of the winter was behind them, and they could look forward to longer days and extended hours of sunlight.

The middle of winter has long been a time of celebration around the world. Centuries before the arrival of the man called Jesus, early Europeans celebrated light and birth in the winter’s darkest days. Many peoples rejoiced during the winter solstice when the worst of the winter was behind them, and they could look forward to longer days and extended hours of sunlight.

In Scandinavia, the Norse celebrated Yule from December 21, the winter solstice, through January. In recognition of the return of the sun, fathers and sons would bring home large logs, which they would set on fire. The people would feast until the log burned out, which could take as many as 12 days. The Norse believed that each spark from the fire represented a new pig or calf born during the coming year.

The end of December was a perfect time for celebration in most areas of Europe. At that time of year, most cattle were slaughtered not to be fed during the winter. For many, it was the only time of year when they had a supply of fresh meat. Besides, most wine and beer made during the year was finally fermented and ready for drinking.

In Germany, people honored the pagan god Oden during the midwinter holiday. Germans were terrified of Oden, as they believed he made nocturnal flights through the sky to observe his people and then decide who would prosper or perish. Because of his presence, many people chose to stay inside.

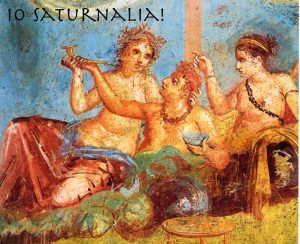

Saturnalia

In Rome, where winters were not as harsh as those in the far north, Saturnalia—a holiday in honor of Saturn, the god of agriculture—was celebrated. In the week leading up to the winter solstice and continuing for a full month, Saturnalia was a hedonistic time, when food and drink were plentiful, and the normal Roman social order was turned upside down. For a month, slaves would become masters. Peasants were in command of the city. Business and schools were closed so that everyone could join in the fun.

Also, around the winter solstice, Romans observed Juvenalia, a feast honoring Rome’s children. Also, members of the upper classes often celebrated the birthday of Mithra, the god of the unconquerable sun, on December 25. It was believed that Mithra, an infant god, was born of a rock. For some Romans, Mithra’s birthday was the most sacred day of the year.

Also, around the winter solstice, Romans observed Juvenalia, a feast honoring Rome’s children. Also, members of the upper classes often celebrated the birthday of Mithra, the god of the unconquerable sun, on December 25. It was believed that Mithra, an infant god, was born of a rock. For some Romans, Mithra’s birthday was the most sacred day of the year.

Is Christmas Really the Day Jesus Was Born?

Early Christian community distinguished between identifying the date of Jesus’ birth and the liturgical celebration of that event. The actual observance of the day of Jesus’ birth was long in coming. In particular, during the first two centuries of Christianity, there was strong opposition to recognizing the birthdays of martyrs or, for that matter, of Jesus. Numerous Church Fathers offered sarcastic comments about the pagan custom of celebrating birthdays when, in fact, saints and martyrs should be honored on the days of their martyrdom—they’re true “birthdays,” from the church’s perspective.

Early Christian community distinguished between identifying the date of Jesus’ birth and the liturgical celebration of that event. The actual observance of the day of Jesus’ birth was long in coming. In particular, during the first two centuries of Christianity, there was strong opposition to recognizing the birthdays of martyrs or, for that matter, of Jesus. Numerous Church Fathers offered sarcastic comments about the pagan custom of celebrating birthdays when, in fact, saints and martyrs should be honored on the days of their martyrdom—they’re true “birthdays,” from the church’s perspective.

The precise origin of assigning December 25 as the birth date of Jesus is unclear. The New Testament provides no clues in this regard. December 25 was first identified as the date of Jesus’ birth by Sextus Julius Africanus in 221 and later became the universally accepted date. One widespread explanation of the origin of this data is that December 25 was the Christianizing of the dies Solis invicti nati (“day of the birth of the unconquered sun”), a popular holiday in the Roman Empire that celebrated the winter solstice as a symbol of the resurgence of the sun, the casting away of winter and the heralding of the rebirth of spring and summer. Indeed, after December 25 had become widely accepted as the date of Jesus’ birth, Christian writers frequently connected the sun’s rebirth and the Son’s birth. One of the difficulties with this view is that it suggests a Christian church’s nonchalant willingness to appropriate a pagan festival when the early church intended to distinguish itself categorically from pagan beliefs and practices.

A second view suggests that December 25 became the date of Jesus’ birth by a priority reasoning that identified the spring equinox as the date of the creation of the world and the fourth day of creation, when the light was created, as the day of Jesus’ conception (i.e., March 25). December 25, nine months later, then became the date of Jesus’ birth. For a long time, the celebration of Jesus’ birth was observed in conjunction with his baptism, celebrated on January 6.

A second view suggests that December 25 became the date of Jesus’ birth by a priority reasoning that identified the spring equinox as the date of the creation of the world and the fourth day of creation, when the light was created, as the day of Jesus’ conception (i.e., March 25). December 25, nine months later, then became the date of Jesus’ birth. For a long time, the celebration of Jesus’ birth was observed in conjunction with his baptism, celebrated on January 6.

Christmas began to be widely celebrated with a specific liturgy in the 9th century but did not attain the liturgical importance of either Good Friday or Easter, the other two major Christian holidays. Roman Catholic churches celebrate the first Christmas mass at midnight, and Protestant churches have increasingly held Christmas candlelight services late on December 24. A special service of “lessons and carols” intertwines Christmas carols with Scripture readings narrating salvation history from the Fall in the Garden of Eden to the coming of Christ. Inaugurated by E.W. Benson and adopted at the University of Cambridge, the service has become widely popular.

When Christmas Was Cancelled

In the early 17th century, a wave of religious reform changed the way Christmas was celebrated in Europe. When Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan forces took over England in 1645, they vowed to rid England of decadence and canceled Christmas as part of their effort. By popular demand, Charles II was restored to the throne and, with him came the return of the popular holiday.

In the early 17th century, a wave of religious reform changed the way Christmas was celebrated in Europe. When Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan forces took over England in 1645, they vowed to rid England of decadence and canceled Christmas as part of their effort. By popular demand, Charles II was restored to the throne and, with him came the return of the popular holiday.

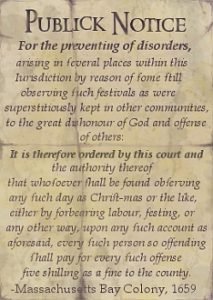

The pilgrims, English separatists that came to America in 1620, were even more orthodox in their Puritan beliefs than Cromwell. As a result, Christmas was not a holiday in early America. From 1659 to 1681, the celebration of Christmas was actually outlawed in Boston. Anyone exhibiting the Christmas spirit was fined five shillings. By contrast, in the Jamestown settlement, Captain John Smith reported that Christmas was enjoyed by all and passed without incident.

After the American Revolution, English customs fell out of favor, including Christmas. In fact, Christmas wasn’t declared a federal holiday until June 26, 1870.

Washington Irving Reinvents Christmas

It wasn’t until the 19th century that Americans began to embrace Christmas. Americans re-invented Christmas and changed it from a raucous carnival holiday into a family-centered day of peace and nostalgia. But what about the 1800s piqued American interest in the holiday?

The early 19th century was a period of class conflict and turmoil. During this time, unemployment was high, and gang rioting by the disenchanted classes often occurred during the Christmas season. In 1828, the New York city council instituted the city’s first police force in response to a Christmas riot. This catalyzed certain upper-class members to begin to change the way Christmas was celebrated in America.

In 1819, best-selling author Washington Irving wrote The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, gent., a series of stories about celebrating Christmas in an English manor house. The sketches feature a squire who invited the peasants into his home for the holiday. In contrast to the problems faced in American society, the two groups mingled effortlessly. In Irving’s mind, Christmas should be a peaceful, warm-hearted holiday bringing groups together across lines of wealth or social status. Irving’s fictitious celebrants enjoyed “ancient customs,” including the crowning of a Lord of Misrule. Irving’s book, however, was not based on any holiday celebration he had attended. In fact, many historians say that Irving’s account actually “invented” tradition by implying that it described the true customs of the season.

In 1819, best-selling author Washington Irving wrote The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, gent., a series of stories about celebrating Christmas in an English manor house. The sketches feature a squire who invited the peasants into his home for the holiday. In contrast to the problems faced in American society, the two groups mingled effortlessly. In Irving’s mind, Christmas should be a peaceful, warm-hearted holiday bringing groups together across lines of wealth or social status. Irving’s fictitious celebrants enjoyed “ancient customs,” including the crowning of a Lord of Misrule. Irving’s book, however, was not based on any holiday celebration he had attended. In fact, many historians say that Irving’s account actually “invented” tradition by implying that it described the true customs of the season.

A Christmas Carol

Also, English author Charles Dickens created the classic holiday tale, A Christmas Carol, around this time. The story’s message- the importance of charity and goodwill towards all humankind-struck a powerful chord in the United States and England- showed Victorian society members the benefits of celebrating the holiday.

The family was also becoming less disciplined and more sensitive to children’s emotional needs during the early 1800s. Christmas provided families with a day when they could lavish attention-and gifts-on their children without appearing to “spoil” them.

As Americans began to embrace Christmas as a perfect family holiday, old customs were unearthed. People looked toward recent immigrants and Catholic and Episcopalian churches to see how the day should be celebrated. In the next 100 years, Americans built a Christmas tradition all their own that included pieces of many other customs, including decorating trees, sending holiday cards, and gift-giving.

As Americans began to embrace Christmas as a perfect family holiday, old customs were unearthed. People looked toward recent immigrants and Catholic and Episcopalian churches to see how the day should be celebrated. In the next 100 years, Americans built a Christmas tradition all their own that included pieces of many other customs, including decorating trees, sending holiday cards, and gift-giving.

Although most families quickly bought into the idea that they were celebrating Christmas how it had been done for centuries, Americans had really re-invented a holiday to fill the cultural needs of a growing nation.

Who Invented Santa Claus?

The legend of Santa Claus can be traced back to a monk named St. Nicholas, who was born in Turkey around 280 A.D.. St. Nicholas gave away all of his inherited wealth and traveled the countryside helping the poor and sick, becoming known as the protector of children and sailors.

St. Nicholas first entered American popular culture in the late 18th century in New York, when Dutch families gathered to honor the anniversary of the death of “Sint Nikolaas” (Dutch for Saint Nicholas), or “Sinter Klaas” for short. “Santa Claus” draws his name from this abbreviation.

Christmas did not start in Germany, but many of the holiday’s traditions began there, including decorating trees. The celebration of Christmas started in Rome at about 336, but it did not become a major Christian festival until the 9th century.

Christmas Facts

- Each year, 30-35 million real Christmas trees are sold in the United States alone. About 21,000 Christmas tree growers in the United States and trees grow for about 15 years before selling.

- In the Middle Ages, Christmas celebrations were rowdy and raucous—a lot like today’s Mardi Gras parties.

- When Christmas was canceled: From 1659 to 1681, the celebration of Christmas was outlawed in Boston, and lawbreakers were fined five shillings.

- Christmas was declared a federal holiday in the United States on June 26, 1870.

- The first eggnog made in the United States was consumed in Captain John Smith’s 1607 Jamestown settlement.

- Poinsettia plants are named after Joel R. Poinsett, an American minister to Mexico, who brought the red-and-green plant from Mexico to America in 1828.

- The Salvation Army has been sending Santa Claus-clad donation collectors into the streets since the 1890s.

- Rudolph, “the most famous reindeer of all,” was the product of Robert L. May’s imagination in 1939. The copywriter wrote a poem about the reindeer to help lure customers into the Montgomery Ward department store.

- Construction workers started the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree tradition in 1931.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2020 meline Ngo

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2020 meline NgoArticle Ti more...

Thank you. God Bless.

i love this faultless post